Federated Learning

By Tianchen Liu

Introduction

Unless you carry the entire server of a cloud platform around as a mobile device using telekinetic superpowers, the usual way cloud platforms train on user data is: upload user data onto the centralized server and start training the model.

But this raises some issues in security and privacy. Suppose you’re using a keyboard that learns from a user’s typing patterns. Your choices for the next word will then be sent to the server. If someone always clicks “Bears” after they type “Go”, then there’s a pretty good chance they’re from Cal. Just like that, there’s leaked information about the user. Any leakage of information from the server or the presence of an adversarial server (say, the server is evil and looks at your data even though it shouldn’t) will cause privacy problems, especially when it comes to sensitive data (e.g. social security number, mother’s maiden name, etc.).

That being said, machine learning is quite literally learning from data. Training a model without real-world user data is pretty much infeasible.

Is there a way where we can train a model from real user’s data while giving nothing away to the server?

Yes there is, and it’s called Federated Learning.

Federated Learning

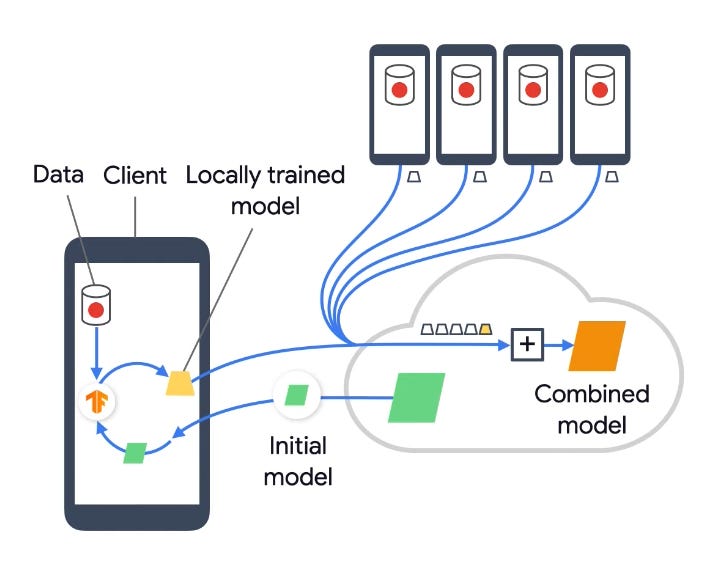

Diagram taken from Google’s YouTube video on Federated Learning

The basic idea can be summarized into one sentence: Instead of bringing user data to the server, we bring part of the training and prediction to the user’s device. On top of the security issues, on-device inference also provides better latency, works offline, and preserves battery life.

The Procedure

Before we get started, let’s address the elephant in the room. Training a model on a device is not a trivial task that most devices can do trivially. In practice, a subset of eligible devices that are idle, currently charging, and connected to a free wireless connection are chosen for on-device model training. You don’t need to worry about a model training in the background when you’re busy playing a 3D game!

The procedure for federated learning is as follows:

The devices will receive a training model (that’s not gigantic, usually just a few megabytes).

The devices train on the local data (usually just a few minutes).

The devices send encrypted updates on the parameters to the server.

The server groups the devices. For each group, the server aggregates the updates it received from the group of devices to perform one update to the current model.

After rounds of training, the new updated model is sent to the devices for on-device testing (again, the theme of decentralization is at play here) and a new round of training.

The frequency of this procedure can be adjusted accordingly, and different devices may be at different stages in a given time - some devices are training while others are testing. After a couple thousand iterations of this procedure, the new tested and truly updated model is ready for mass distribution.

Secure Aggregation

The on-device training uses the same techniques that we know and love, such as Stochastic Gradient Descent, etc. So let’s shift our focus to step 4 of the procedure above. A natural question is why are we grouping the devices? Why are we “averaging” the updates and then performing the “averaged” update? Why can’t we just update it one by one?

Well, let’s see what happens when, again, an evil server receives a single update. Then it could reconstruct private training data that caused the update by just coming up with data that would cause a similar update.

Secure aggregation handles this problem. The remainder of this blog will discuss the secure aggregation problem. It’s going to get a little bit technical, but I’ll explain it on the way.

The Procedure

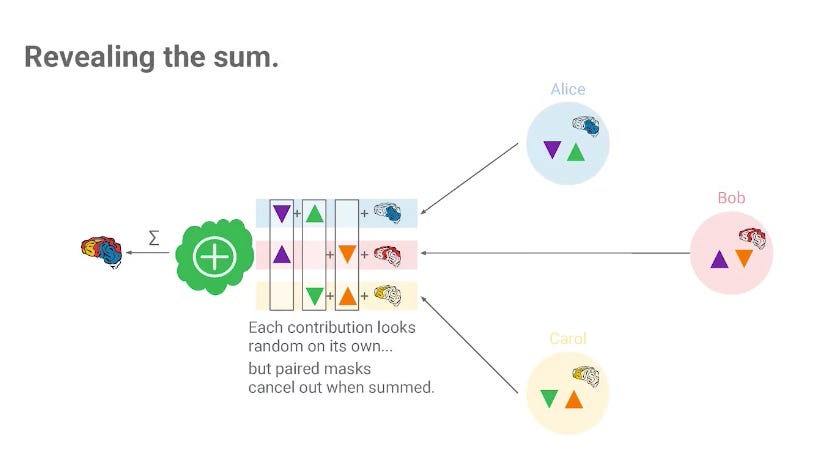

Let us first think about what exactly is an “update”. It’s a length nnn vector, where nnn is the number of parameters for this model. The main idea is that we can obfuscate the update by adding the update vector with another randomly generated “mask vector” with the same length as the update vector.

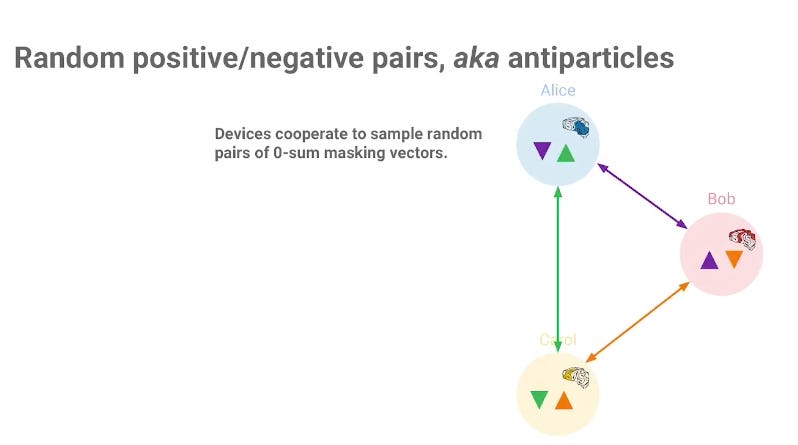

For simplicity of explanation let group size be three. The three devices cooperate to generate random mask vectors and their negations (shown as the inverted triangle) and are distributed in the group.

Diagram taken from the keynote for the Secure Aggregation paper

This way, when the server aggregates the update together, the mask vectors cancel out, and the results are cleanly the aggregation of the updates.

Diagram taken from the keynote for the Secure Aggregation paper

Unfortunately, this is way easier said than done. Let’s think about just exactly how big this “mask vector” should be. Keep in mind that the update vector is length n, where n is the number of parameters in the model. Therefore the mask vector needs to be length n as well.

What’s more, in practice the group size is in the order of thousands and more, so we’ll be needing to coordinate thousands of length n mask vectors with thousands of users, where the vectors are as big as a neural network model! To make matters worse, this procedure has to be discreet between the two parties - because there’s no point in doing all this if the mask vector is already exposed publically (to the server). This is going to cost a lot of resources and time. Is there a way to get around this problem? Behold, the ---

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

The idea to solve this issue is: instead of letting two devices discreetly agree on a length nnn vector, we’re going to let two devices discreetly agree on one single integer instead. Then, we’re going to use that integer as a seed for a (pseudo)random number generator (PRNG). Both parties call the PRNG with that specific seed nnn times and hence would generate the same length nnn vector to use as the random mask vector.

Now the question is: How do we let two parties come up with the same number, secretly? That’s where the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange comes to play. Intuitively, the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange allows two parties to come up with the same secret number by coordinating with each other publicly (low cost) but not revealing anything about this secret number.

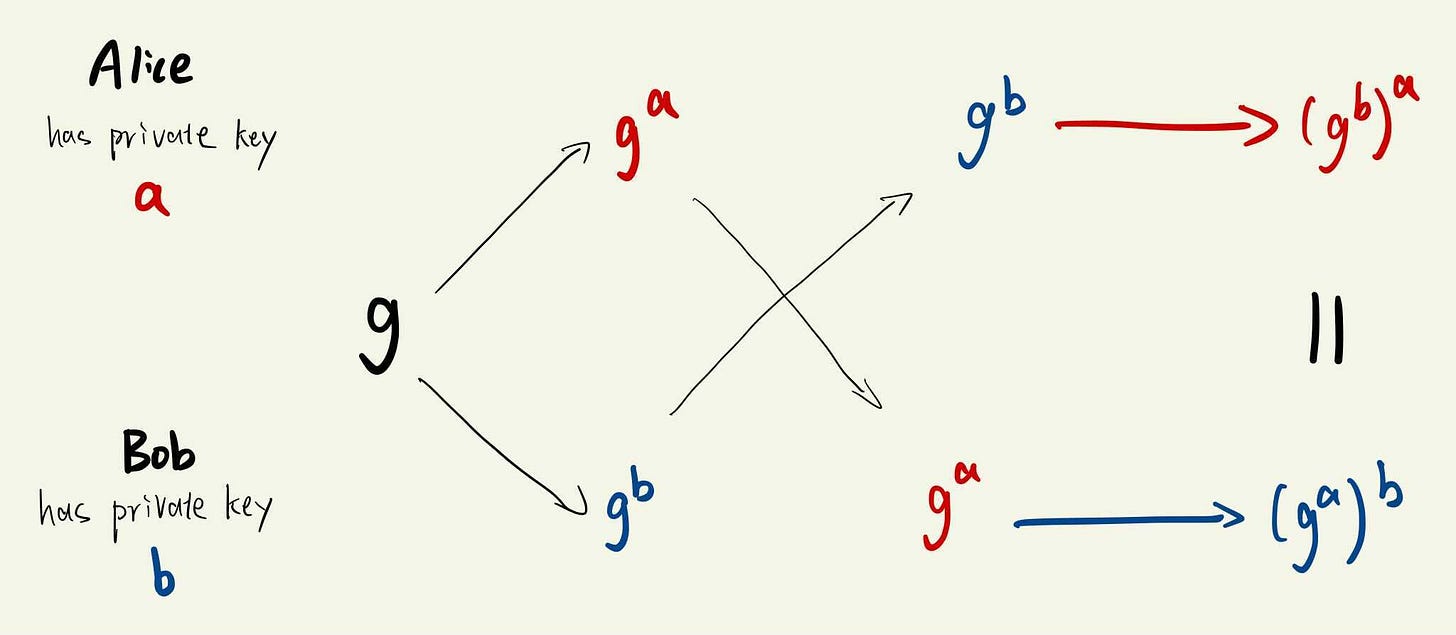

All following operations are within the “mod p space”1 (i.e. we mod p all the time). The backbone of Diffie-Hellman is the fact that discrete logarithm (ga≡x mod p, know g and x, what’s a?) is computationally intractible with large p. Let g be a number such that (g0, g1, g2,… ) hits every number in (1,2,…,p−1).2 g and prime p are public.

Alice and Bob choose their own private key a and b respectively.

Alice (publicly) sends Bob ga and Bob raises it to the bth power to obtain gab; Bob (publicly) sends Alice gb and Alice obtains gba the same way.

They now both obtained the same integer while never revealing any information about this number (it is intractible to obtain a given (ga, g), remember we’re in ”mod p space” here so we can’t just take log and call it a day).

Using the server as a coordinator (recall that it’s ok for the server to see (ga, gb , …) and the procedure above, we can securely distribute the common secrets that are integers? Now we use the secret integer as a seed for a (pseudo)random number generator and call the generator nnn times. I hope you are convinced that this is much more efficient than sending gigantic vectors around thousands of devices.

With this in mind - the fact that we’re using a secret integer to “represent” the mask vector, we can tackle the following problem: what if someone’s WiFi goes down while doing all this?

Secret Sharing

The main idea behind this notion is that we can embed a secret onto a polynomial, which enables us to share only parts of the secret with other users, such that the entire secret can only be reconstructed by collecting parts of the secret from other users

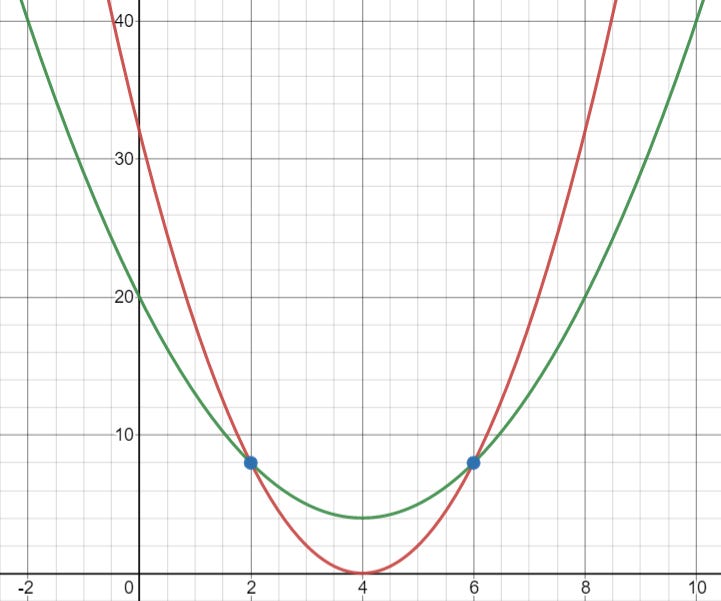

Fact: For any degree d polynomial, you can successfully retrieve the polynomial if and only if you know at least d+1 points that the polynomial passes through.

A simple intuition of this fact is the case where d=1. The polynomial is just a straight line, and you need at least two points to pin a line.

Two points are not enough to fix a parabola (degree 2 polynomial).

Suppose we have a group of n devices, and we have a threshold k for the minimum number of active participants (we’re ok to continue as long as no more than n−k users drop out midway).

Recall from the previous part that we’re using a secret integer to represent the mask vector.

Each user randomly generates a degree k−1 polynomial whose y-intercept is the secret integer and randomly picks nnn points on the polynomial.

Each user shares the nnn points to the size nnn group, such that every user receives one unique point.

If someone drops out midway, the server asks online users for shares of the offline user’s polynomial and interpolates it to retrieve the polynomial, by doing so it obtains the y-intercept - the secret integer.

As long as the threshold k is big enough, the protocol is still secure3

In Conclusion

In this blog, we introduced a new type of machine learning procedure where the training is distributed to the users. We then talked about a solution to securely aggregate all the updates. Using Federated Learning, we can train models offline with better latency, and never worry about data breaches because the training data never got out of our device.

Federated Learning is a relatively new field in machine learning and there are many open problems, such as how to make the model more robust in order to handle the presence of adversarial users - e.g. what if the user flips all the labels or sends random vector as the update vector? How do we make the model fairer - measured as the uniformity of performance - towards all users? Et cetera. A single blog post can’t address everything about this topic, so feel free to look at the relevant papers below if you’re interested!

References

- \((\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z})^\times\)

In Group Theory terms: Let g be a generator for a multiplicative group of integers modulo prime p

There’s a security problem if a device sent its data late such that the server already called for shares to retrieve the secret integer, but this issue is solved using essentially the same ideas but a little bit messier. The keynote for the secure aggregation paper explains it wonderfully.